“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Romeo and Juliet, act II

My name is Michael. That name is a label, a symbol that stands for my social identity, but not my essence.

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth [creation].

The named is the mother of ten thousand things…

The mystery of the “Way,” [our essence], can never be explained or named, but we can live it… For the Taoist, nature and spirit interpenetrate. In spirit there is nature and in nature, there is spirit {our essence].

Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, 400BC

Translated by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English

The explanation or name is, by definition, an abstract image, a metaphor, something the metaphor is not. The word is not the thing. Like our name, gender is a social construct, not our essence.

Today it appears ‘politically correct’ for my identity as a scuba diver to show up at a ballet class wearing a mask and fins. I’m identified as a scuba diver, therefore I have the right to expect, and even demand, that others respect and adapt to my preference, my choices. Forgetting that society is a stage, and our egos or social identity is a costume or character performing in this theater, we miss that context and character are two sides of a single coin. Identity and context are inseparable. To participate in the performance, we are expected to show up in the approved costume and deliver our lines, or behave, in a manner most appropriate to that social context, be that a dancer, academic, or boilermaker. Each stage demands a different costume identity. I dress differently for a formal wedding than a rave party or waterskiing. But, not anymore. My chosen costume or social identity is now defining the context.

The social justice movement insists that the stage and script called society or culture be rewritten to accommodate my longing, desire, unhappiness or discomfort with the social interpretation or role God or biology predefined. The entire culture, its structure, definitions, and laws must now be reorganized to accept and respect any identity costume I wish to be cast as, rather than my adapting my behavior to express those qualities the role I’m auditioning for require. Of course, I expect to be tar-and-feathered for this simple simile, but to me, this feels like the tail is wagging the dog.

I’m advocating that switching costumes does not represent real or fundamental change. On the contrary, one role is subject to the same prejudgments, comparisons, pressures and therefore stress and trauma as another, just different. Rearranging the set props or costumes is not stepping off the stage, as Krishnamurti’s “complete attention” suggests below. What we call our ego or social identity is an artifact of our vast capacity to imagine, which as David Bohm described, operates too fast for us to keep track of what we are doing. We lose track and assume (falsely reify) what is imagined to be a reality independent from thought. If the ego is an illusion, gender, distinct from biological sexual differences is a subset of that illusion. Swapping one illusion for another does not touch the underlying conflict which is the false or delusional nature of social images. This may, I suggest, account for the pervasive unhappiness, stress, and conflicts many Trans people continue to experience, a vulnerability I propose is being exploited. See Corporate Exploitation of Gender. For example:

In 2018 the UK reported a 4,400% rise in teenage girls seeking gender treatment.

More than 40% of transgenders attempt suicide with a higher portion resulting after reassignment surgery.

As of 2019, there were over 25,000 adverse reports including 1500 deaths on Lupron products for puberty blockers, endometriosis, and prostate cancer.

“I thought it was about inclusion and tolerance.”

“I thought these rainbows were nice. I did not see the dark side of this.”

“I have to do something crazy that will make me feel happy.”

“This is the sweeping nature of gender ideology that is taking over our entire society”

Cut – Daughters of the West Documentary

Essence is not a mental image, a name, what is ‘known,’ or our social identity. Essence is nameless. Embodied essence is our true nature, which is nature, unfolding creation. The name we ‘know,’ as Lao Tsu observes, is the mother of ten thousand things; conflict, confusion, suffering and endless wars. Juliet’s lament endures. Just look at what is happening with gender politics today.

Our true nature could be compared to the sky, and the confusion of the ordinary mind to clouds. Some days the sky is completely obscured by clouds.

We should always try and remember: the clouds are not the sky, and do not “belong” to it [our essence, the sky, is not our social identity, clouds]. Clouds only hang there and pass by in their slightly ridiculous and non-dependent fashion. And they can never stain or mark the sky [our essence] in any way.

So where exactly is this Buddha nature? It is in the sky-like nature of our mind. Utterly open, free, and limitless, it is fun, damentally so simple and so natural that it can never be complicated, corrupted, or stained, so pure that it is beyond even the concept of purity and impurity. To talk of this nature of mind as sky-like, of course, is only a metaphor that helps us to begin to imagine it’s all embracing boundlessness; for the Buddha nature has a quality the sky cannot have, that of the radiant clarity of awareness. As it is said: It is simply your flawless, present awareness, cognizant and empty, naked and awake.

Sogyal Rinpoche

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

The name that can be named, our social identity, are clouds. The nameless is essence, infinite sky empty of clouds, naked presence, a state that is free of conformity or its comparisons.

What we are trying in all these discussions and talks here is to see if we cannot radically bring about a transformation of the mind. Not accept things as they are… But to understand it, to go into it, to examine it, give your heart and your mind with everything you have to find out a way of living differently?

When you put that question, because you are serious, because you are intent, then you are aware of the whole process of the observer, [our ego or social identity]. Which means that you are totally attentive, completely attentive. And in that attention there is no border created by the center. When there is complete attention there is no observer. The observer comes into being only when, in that look, there is inattention which is distraction.

In that [complete] attention there is no seeking at all. And therefore there is no effort [no comparison, no identity]. The mind becomes extraordinarily alert, active, silent. Such a mind is the religious mind. And such a mind has an activity totally different, at a different dimension which thought can never possibly reach.

J. Krishnamurti

PBS Broadcast, Ojai, California, 1966

Krishnamurti’s insight; “when there is complete attention there is no observer,” is perhaps one of his most distilled of an estimated 250,000 pages of collected works. The observer being ‘me,’ my social identity or ego. That image comes into being when there is inattention, which is distraction. In this context, distraction is our normal default state, compulsively wondering if we belong.

“To me,” or “not to me,” that is the question? But, what’s in a me? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. If there were no expected norms to compare, “I should be this and not that,” how would we dress, speak, or behave? Would our identity be driven by essence, image, or social context, without identifying with any of these? Confusing these, assuming that mental images truthfully represent essence, is a very slippery slope, indeed.

I’m suggesting; with complete attention, all the social pressure to ‘be’ this way or that, comparison and conformity, disappear. A state of mind free from comparison and its projections is the classic definition of “Flow,” the optimum state for learning and performance, or what athletes call “The Zone.” Flow, or being in The Zone is definitely not insisting, demanding, that I’m being forced “play” the wrong role, or hate the costume central casting predefined. Comparison-free presence implies not identifying with the costume or the stage. Simply discovering and expressing essence, the true hero’s journey.

Complete attention means having no mental image to compare, which means no identity, no name that can be named, no possibility of embarrassment. With no image to uphold, my identity would simply be flawless, present awareness, cognizant and empty, naked and awake, “non-duality” in today’s hip parlance. Perhaps this state, free from ego, is the optimum goal of every individual, rather than each individual demanding that the entire culture turn itself inside out to meet whatever preferences or color of lipstick we may choose today? Ego and social identity are costumes.

I identify as many things; photographer, father, writer, American, entrepreneur, husband, documentary filmmaker, aging male, medium height, of average body and build, Caucasian, English speaking, somewhat kind, and many other qualities, all categories or sub-categories, each taking center stage in the play called society on cue. Others identify as lawyers, PhDs, bankers, physicians, dancers, artists, musicians, mothers, midwives, children, teachers… You get the picture.

Each of these categories is an abstract mental metaphor, labels that stand for a collection of specific behaviors that define a particular quality, character or social role. Ego might be defined as the relative constellation of these felt mental metaphors as we desperately attempt to convince others that we really are what we are pretending to be. So committed to the role that we forget we are playing it. Comparison creates the ego.

Being human embodies a unique constellation of sensory, emotional, and cognitive capacities that together project a very specific virtual reality in our brain, one we share with all other humans, biologically male and female. This virtual reality is fundamentally different than bats, bunnies, trees, snakes, whales, and fruit flies, different from all the other 2.16 million species on Earth. The perceived reality of each species is therefore unique. We are human, not German or Republicans, Buddhists, accountants, males or females, though brain, body, and hormonal differenced imply slight but profound differences. A male can be just as empathic and nurturing as a female without high heels. Female breasts are designed to be suckled. The costume is irrelevant.

In our mental enchantment, and desperate need to belong, we forget what human feels like and mistake our social role for essence. The question is; if we were not identified with our personal collection of deeply conditioned social roles, good little boys and girls, what would we then identify with? For all the reasons that we play our roles so well, this question is taboo, concealed. David Bohm explores this forbidden question;

The problem with the self, there is an assumption or concept which, if it were real, would be extremely important, and would be the highest value of all things because you just think of the word, ‘self,’ it’s basic meaning is the quintessence, the essence of all essences and that would, of course, have supreme value. If we assume there is a self, this stirs up the whole mind and brain inside so it feels, just from that assumption, that something is going on inside which corresponds to this assumed self and gives it an apparent reality. Once it has been assumed that this self is real and not merely an image, its attributed reality, then it takes first priority and everything else comes second, so everything is distorted… and this distortion becomes universal.

The main point is that we don’t really understand the nature of our thought process; we’re not aware of how it works and it’s really disrupting not only our society and our individual lives, but also the way the brain and nervous system operate, making us unhealthy or perhaps even in some way damaging the system. It is recognized that thought, rational, orderly, factual thought, such as in doing proper science, is valuable but the dangerous type of thought is self-centered thought.

At first sight one might wonder why self-centered thought (that all our social roles imply) is so bad. If the self were really there, then perhaps it would correct to center on the self because the self would be so important, but if the self is a kind of illusion or image, at least the self as we know it, then to center our thought on something illusory which is assumed to have supreme importance is going to disrupt the whole process, and it will not only make thought about yourself wrong, it will make thought about everything wrong, so that thought becomes a dangerous and destructive instrument all around.

Because this image of the self, the concept of the self, is assumed to be so all-important, the brain starts to develop a defense mechanism to “defend this image against perception of its falseness or illusory character.” You can see this very easily that if somebody says, “You are an idiot,” there is immediately a response to say, “I’m not an idiot.” It’s painful to have an image of yourself as an idiot, therefore you’ll say, “You’re wrong,” and you may start adopting all sorts of explanations to show that you are OK and the other person is the idiot. This is a minor point compared with the tremendous energy that comes in when the very existence of this image is apparently threatened by some evidence that it is only an image, it’s only an illusion. Then, the entire brain starts to be disrupted, the brain and nervous system, and (as) a result a defense mechanism comes in just to block it or to wipe it out or to turn attention somewhere else, just simply to make it almost impossible to go any further into this question, you see – forget about it and find yourself doing something else, any number of defenses. And, you see, it’s clear that when somebody comes along and says that this is an illusion or this isn’t that real, that this defense mechanism is going to be provoked into action and this, then, becomes the principal difficulty in seeing the illusion.

The major form of defense is simply concealment of what’s going on, because if we could see what’s going on it would be obvious it’s an illusion; it’s like seeing through the trick of the magician. You may also conceal by just denying that it’s so, and asserting something else. Therefore, we are not conscious, certainly of the defense mechanism, because this process of concealment itself has to be concealed in order to make it effective, and therefore, the major part of defense consists in making the whole process unconscious.

Our enchantment is so convincing the very act of questioning or applauding the validity of these qualities, beliefs or behaviors we identify with, “something” inside feels wounded or flattered. What is that “something?” If we did not identify with a particular image, would there be that pleasure, pain, arrogance, shame, embarrassment or pride? I don’t think so. “Sticks and stones may break my bones but dream images can never hurt me. Unless we forget that the costume is only a costume.

Perhaps identity isn’t really the image, rather it is the feeling of acceptance or rejection, that we do or don’t belong that is this “something” that expresses as hurt or pleasure. Maybe the hurt feeling or the pleasure creates the image that reincarnates, and we identify with that, rather than the image-ego actually being hurt. Do images have feelings? Or are feelings and needs ‘real,’ which elicit abstract mental images to represent them? Returning to Bohm;

It is being suggested that the self (our personal social roles) is not the source of thought but rather, thought is the source of the self. That may seem paradoxical to our ordinary experience, but at least we can make it reasonable. We are saying that the assumption of the self creates inside, a kind of image of the self, corresponding to that assumption, with great power. That image is attributed reality and we get a feeling that it’s real; therefore, we assume the assumption that the self is the thinker, the source of thought, and there is that which he is thinking about. In this view or assumption, the things which really are solidly existent are the thinker and what he is thinking about. Thought is a very ethereal, almost non-existent thing.

What is being suggested instead is that the thought process is real, it’s going on in the brain and nervous system, and this thought process contains in it the assumption of a thinker who produces thought. It is as if thought is producing a television program of a thinker producing thought and the mind is watching that program so intently that it takes that to be the reality. Thought now says, “I am very modest; I am serving the thinker,” but in fact it is serving itself because it produces this thinker and then does what this thinker wants.

Creating these images is the normal function of the thought process. Dangerous habits of self-deception creep in when we falsely assume that the image is not a dream, and treat that image as a ‘real’ thing independent of thought, mental magic, reification. If we were not identified with our personal collection of conditioned social roles, what would we identify with or as?

One’s relationship with another is based on memory. Would you accept that? On the various images, pictures, conclusions I have drawn about you and you have drawn about me. The various images that I have about you, wife, husband, girl or boy or friend and so on, there is always image making.

This is simple, this is normal, this actually goes on. When one is married, or lives with a girl or a boy every incident, every word, every action creates an image. No? Are we clear on this point? Don’t agree with me please I am not trying to persuade you to anything. But actually you can see it for yourself. A word is registered, if it is pleasant you purr. It is nice. If it is unpleasant, you will immediately shrink from it and that creates an image. The pleasure creates an image; the shrinking, the withdrawal creates an image. So, our actual relationship with each other is based on various subtle forms of pictures, images and conclusions.

When there is an image like that, she has and you have, then in that there is division and the whole conflict begins, right? Where there is division between two images, there must be conflict, right? The Jew, the Arab, the Hindu, the Muslim, the Christian, the Communist, it is the same phenomenon. It is a basic law, that where there is division between people there must be conflict. The man may say to the woman or the woman may say to the man “I love you”, but basically, they are not related at all.

Then the factor arises, can all this image-making, tradition and all that end, without a single conflict? Do you understand my question? Are you interested in this? What will you pay for it? That is all you can do. By paying something you think you will get it. Now, how can this mechanism of image making. Not just Image making, that is the desire for certainty, the tradition, the whole structure of that, can that end?

J. Krishnamurti

Brockwood Park 2nd Public Dialogue, 31st August 1978

We are so deeply conditioned to perform and beg for acceptance, and belonging, that we mistake the costume, role, or image for our living essence, our authentic nature. “Don’t listen to the words, believe in the metaphors,” advises Marshall Rosenberg, founder of Nonviolent Commination. “Experience and respond only to the feelings and needs behind the image.” Feeling and needs express something alive. The words, the roles we identify with are placeholders that represent something else. Essence.

Identity is a social construct, and like the ego, represents a mental costume worn on a given social stage, as an actor or actress, pretending to be something. Our social self or ego is a coping pattern created to navigate the demands of cultural pressures to limit and control each human being, demanding obedience and conformity. Behave this way and we are accepted, praised, and rewarded. Act another way and we are punished, rejected, in the family, in school, church, and nearly every other social structure. Conformity and unquestioned obedience dominate. Our ego emerges from this pressure.

Sure, everyone should see through this ruse and step off the stage, not simply demand that we rearrange society to conform to everyone’s declared preference, which fundamentally, changes nothing. Before asking any questions of the Gods, the Oracle of Delphi would insist that visitors investigate themselves, the essential prerequisite for understanding the world. “Know thy self.” Plato transmitted this phrase in his dialogues, suggesting the importance of looking inwards before making any decisions or moving forward. Easier said than done notes Bohm;

Because this image of the self (and our false identity with that image, rather than essence,) is assumed to be so all-important, the brain develops a defense mechanism to “defend this image against the perception of its falseness or illusory character.”

Self-knowledge, much deeper than gender, ego or other social images, is the essence of human maturity and our greatest responsibility.

Knowing what we actually are, aligning and expressing essence, not simply swapping social images, not only helps each of us, it helps the world. But, we don’t identify with essence, we identify with the social costume, and in that defense invent and spread pervasive and very dangerous forms of self-deception in our wake. Real social transformation demands more than changing one’s costume. It demands complete freedom from identifying with them.

M

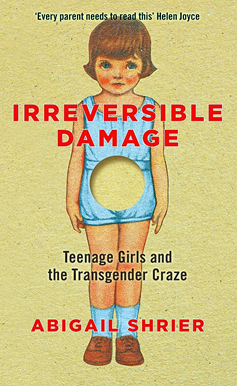

The book Silicon Valley tried to kill: ABIGAIL SHRIER’S investigation into the exploding numbers of girls wanting to change sex has caused an outcry in America – but her story must be heard.

By Abigail Shrier For The Mail On Sunday

The increasing number of young girls wanting to switch gender has become an explosive subject as parents, scientists and campaigners warn of the irreversible, life-changing dangers.

When ABIGAIL SHRIER, a writer for the Wall Street Journal, investigated the issue for a book, her first prospective publisher pulled out following protests by staff. Then, amid a furious row over free speech, an English professor at one of America’s top universities suggested the book should be burned. And when Shrier was interviewed for a podcast hosted by Spotify, staff at the streaming giant threatened to walk out. And although Amazon sells her book, it has refused to let Shrier’s publisher buy online adverts. In face of these attempts at censorship, Shrier has condemned what she calls ‘tyranny’s advance’, saying: ‘This is what censorship looks like in 21st Century America.

‘It isn’t the government sending police to your home. ‘It’s Silicon Valley oligopolists implementing blackouts and appeasing social-justice mobs, while sending disfavoured ideas down memory holes. ‘And the forces of censorship are winning.’

Lucy had always been a ‘girly girl’, her mother told me. As a child, she loved high heels and frilly dresses. Dressing up was a favourite game, and she had a trunk full of gowns and wigs she would dip into, inhabiting an assortment of characters – every one of them female. She adored Disney princess movies, especially The Little Mermaid.

Lucy was precocious, reading early. But by 11, her anxiety spiked. The waters of depression rushed in. Her affluent parents took her to psychiatrists and therapists, but no amount of talking therapy or drugs levelled her social obstacles: the cliques that didn’t want her or her tendency to fluff social tests casually administered by other girls.

Boys gave her less trouble, and she had male friends and boyfriends throughout school. Lucy’s ups and downs eventually resolved in a bipolar diagnosis. Arriving at university, she was invited to state her name, sexual orientation and gender pronouns. Lucy spotted the new opportunity of social acceptance, a whiff of belonging.

When her anxiety flared later that autumn, she decided, with several of her friends, that their angst had a fashionable cause: gender dysphoria – a distressing mismatch between one’s birth sex and the person they feel they are. Within a year, Lucy had begun a course of testosterone. But her real drug was the promise of a new identity.

A shaved head, boys’ clothes, and a new name formed the baptismal waters of a female-to-male rebirth. The next step would be ‘top surgery,’ a euphemism for a double mastectomy.

I came across Lucy’s story after writing in the Wall Street Journal about the new laws on the use of gender pronouns, under the headline The Transgender Language War. In October 2017, my state, California, had enacted a law backed by possible jail sentences for healthcare workers who refused to use patients’ requested gender pronouns. New York had adopted a similar law, which applied to employers, landlords and businesses. Both laws are unconstitutional, violating the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech.

The increasing number of young girls wanting to switch gender has become an explosive subject as parents, scientists and campaigners warn of the irreversible, life-changing dangers. When Ms Shrier investigated the issue for a book, her first prospective publisher pulled out following protests by staff.

Lucy’s mother saw my article and found something in it: hope. She contacted me under a pseudonym and asked me to write about her daughter. When I asked if she was sure Lucy wasn’t feeling gender dysphoria, she explained that her daughter had ‘never even expressed any discomfort over her body… and she’d always dated boys’.

She said Lucy had discovered this identity with the help of the internet, which provides an endless array of transgender mentors who coach adolescents in the art of slipping into a new gender identity – what to wear, how to walk, what to say. Which online companies sell the best breast binders (a breast-compression garment, worn under clothes); which organizations send them for free and guarantee discreet packaging so that parents never find out; how to persuade doctors to supply the hormones you want; how to deceive parents – or, if they resist your new identity, how to break away entirely.

Gender dysphoria is characterized by a severe and persistent discomfort in one’s biological sex. It typically begins in early childhood, ages two to four, though it may grow more severe in adolescence. But in nearly 70 per cent of cases, childhood gender dysphoria resolves.

Historically, it afflicted about 0.01 per cent of the population, and almost exclusively boys. Before 2012, there was no scientific literature on girls aged 11 to 21 ever having developed gender dysphoria. In the past decade, that has changed dramatically.

The Western world has seen a sudden surge of adolescents claiming to have gender dysphoria and self-identifying as transgender. In Britain, Canada, Sweden and Finland, clinicians and gender therapists began reporting a dramatic shift in the demographics of those presenting with gender dysphoria, from predominately pre-school-aged boys to predominately adolescent girls.

In Britain, in 2018, there was a 4,400 per cent rise over the previous decade in teenage girls seeking gender treatments. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of gender-reassignment surgeries for girls in the US quadrupled, with people born female suddenly accounting for 70 per cent of all such operations.

Why? What happened? How did the sex ratio flip, from overwhelmingly boys to majority adolescent girls?

In Britain, in 2018, there was a 4,400 per cent rise over the previous decade in teenage girls seeking gender treatments. I was an opinion writer, not an investigative reporter, so I put Lucy’s mother in touch with another journalist. But her story remained stubbornly lodged in my brain. Three months later, I got back in touch with her.

I spoke to endocrinologists – doctors who specialise in glands and hormones – psychiatrists, world-renowned psychologists specialising in gender dysphoria, psychotherapists, transgender adolescents and transgender adults. The more I learned about the adolescents who suddenly identify as transgender, the more haunted I became by one question: what’s ailing these girls?

In January 2019, the Wall Street Journal ran my article, When Your Daughter Defies Biology. I was flooded with emails from readers who had experienced with their own children the phenomenon I had described, or had witnessed its occurrence at their children’s schools – clusters of adolescents, suddenly discovering transgender identities together, begging for hormones, desperate for surgery.

Transgender activists attacked me online, so I offered them the opportunity to tell me their stories. I spoke to anyone who had something to offer on this issue. Their responses formed the basis of my book about the transgender craze.

I conducted nearly 200 interviews and spoke to more than four dozen families of adolescents, as well as transgender adults – those who present as women and those who present as men. Indeed, some small proportion of the population will always be transgender. They describe the relentless chafe of a body that feels all wrong, a feeling that has dogged them for as long as they can remember. They are kind, thoughtful and decent. For their honesty and courage, they easily won my admiration. They have very little to do with the current trans epidemic plaguing teenage girls.

Closer to the mark are the Salem witch trials of the 17th Century, the nervous disorders of the 18th Century, and anorexia nervosa, repressed memory, bulimia and the self-harm contagion in the 20th Century.

At the forefront of all this are adolescent girls. Their distress is real, but their self-diagnosis is flawed – more the result of encouragement and suggestion than psychological necessity. Three decades ago, these girls might have hankered for liposuction. Two decades ago, they might have ‘discovered’ a repressed memory of childhood trauma or multiple personality disorder. Today’s diagnostic craze isn’t demonic possession – it’s gender dysphoria.

For these girls, trans identification offers freedom from anxiety, it satisfies their deep need for acceptance, along with the thrill of transgression, egged on by their peers, therapists, teachers and internet influencers.

And its ‘cure’ is not exorcism or purging. It’s testosterone and ‘top surgery’: a lifetime of hormone dependency and disfiguring surgeries. No adolescent should pay this high a price for having been, briefly, a follower of this contagion. The fact is, as a population, adolescent girls today are in a lot of pain.

Teenagers are in the midst of a mental health crisis, evincing record levels of anxiety and depression and self-harm. The number diagnosed with clinical depression grew by 37 per cent between 2005 and 2014. And the worst hit, experiencing depression at a rate three times that of boys, were teenage girls. Why the sudden spike?

Social media is one answer. Anorexia, self-harm and suicide have all increased dramatically since the arrival of the smartphone. Posting online one’s experiences with any of these afflictions offers the chance to win hundreds, even thousands, of followers. Identifying as transgender offers the same.

Many adolescent girls who fall for the transgender craze lead upper-middle-class lives. They are often top-grade students, notable for their agreeableness, companionability and utter lack of rebellion. They’ve never smoked a cigarette; they don’t ever drink. They’ve also never been sexually active. Many have never had a kiss. Their bodies are a mystery to them.

Anxious, depressed, awkward and afraid, they sense a dangerous chasm between the unsteady girls they feel they are, and the glamorous women social media tells them they should be. Bridging that gap feels hopeless.

Pornography also plays a role. Violent porn – readily available to children on platforms such as Pornhub – terrifies young girls about men and the prospect of sex with them.

Violent porn – readily available to children on platforms such as Pornhub – terrifies young girls about men and the prospect of sex with them.

Sasha Ayad, a therapist whose practice is largely devoted to trans-identifying adolescents, says: ‘The kids that I work with are often pretty freaked out by porn… In some cases, porn played a big role in their new adopted identity.’ Many adolescent girls identifying as transgender don’t actually want to become men. They simply want to flee womanhood like a house on fire, their minds fixed on escape, not on any particular destination.

They feel alienated from their bodies and the changes brought by puberty: acne, periods and breast development and uncomfortable attention from men. They might be forgiven for adopting the contemporary creed: ‘There must be a pill for this.’

After all, there is a pill for all ills – Ritalin for inattention, opioids for pain, Xanax for nerves. Testosterone for female puberty. Among the parents who contracted me were two lesbian mothers with a daughter, Julie.

A talented ballet dancer, she was ‘pretty girly and feminine, with no history of gender dysphoria, either as a child or even through puberty’. That is until Julie joined the GayStraight Alliance, a popular club at school, although she identified as straight. There, she met Lauren, and Julie seemed in thrall to her.

When Lauren came out as transgender, Julie toyed with adopting that identity, too, unknown to her mothers. Without their knowledge, Julie’s teachers and friends all began referring to her as a male student and by her new male name. Julie began to lead a kind of double life. Her parents did not know that she was intensively watching trans influencers on YouTube. But they sensed their daughter was slipping away.

At 18, Julie moved out, began a course of testosterone and abruptly cut off contact with her parents. It was only through a friend who followed Julie’s Instagram account that they learned she’d undergone a double mastectomy. They saw a picture of her, straight after her surgery, lying in the hospital bed ‘talking about how this is the best day of her life… and 400 of her [internet] cheerleaders saying, ‘Yay’, ‘Awesome job’, ‘We’re so proud of you’

Like freezing your eggs, blocking puberty with drugs is presented to young women as simply allowing them to put nature on hold while keeping their options open – a neutral, low-risk intervention. But is it?

A teenage girl whose body does not go through the same biological changes as her peers’ is likely to feel more alone, more alienated from womanhood – not less.

No surprise, then, that in a clinical trial, 100 per cent of children put on puberty blockers moved on to cross-sex hormones. That is a stunning statistic, especially considering that when no intervention is made, roughly 70 per cent of children will outgrow gender dysphoria, contradicting the claim of activists that gender identity is innate and ‘immutable’.

Aside from alienation, there are multiple physical dangers from taking puberty blockers: suppression of normal bone density development and greater risk of osteoporosis, loss of sexual function, interference with brain development and possibly suppressing peak IQ. If an adolescent moves straight from puberty blockers to cross-sex hormones, infertility is almost guaranteed. And what effect do sex hormones, such as testosterone, have?

In 2007, there was one gender clinic in the US. Today, there are more than 50, many prescribing testosterone to girls on their first visit on an ‘informed consent’ basis, with no referral or therapy required. For some girls, testosterone can feel like nothing short of a miracle: it suppresses anxiety and even lifts depression and makes it harder to cry. But there are physical effects. After some months on testosterone, a young woman’s voice will start to crack. She’ll develop acne. She may experience male-pattern baldness. Her nose will round, and her jaw will square, and her muscles will grow. After a few months, these changes become permanent.

If a girl regrets her decision and stops taking testosterone, her extra body and facial hair will likely remain, as will her deepened voice, and possibly her masculinised facial features. Testosterone also thickens the blood. There is some indication that women on high doses of testosterone may have nearly five times the risk of heart attack than other women have, and two-and-a-half times that of men.

Often a young woman’s dysphoria increases with testosterone, since even with a man’s voice, body hair, squarer jaw, rounder nose and full beard, she doesn’t look exactly like a man. She still has breasts, after all.

The number diagnosed with clinical depression grew by 37 per cent between 2005 and 2014. Why the sudden spike? Social media is one answer. Anorexia, self-harm and suicide have all increased dramatically since the arrival of the smartphone. So she may go on to have a double mastectomy performed for no medical reason, simply based on her wishes. She will have lost the capacity to breastfeed.

As plastic surgeon Dr Patrick Lappert told me, there is ‘no other cosmetic operation where it is considered morally acceptable to destroy a human function. None’. And yet in California, this surgery is offered to girls aged 13.

Relatively few female-to-male transgender people pursue ‘bottom surgery’– which is probably a good thing. I have talked to enough transgender-identifying people who know someone who has suffered a botched phalloplasty – or suffered one themselves – to fuel a lifetime of nightmares.

After all this risk and untold sacrifice, at least the patient’s dysphoria – the supposed cause of her distress – is gone, right? In fact, there are no good long-term studies of this population indicating that either gender dysphoria or serious thoughts about suicide diminish after medical transition.

A leaked 2019 report from London’s Tavistock and Portman Trust gender clinic showed that rates of self-harm and suicidal thoughts and actions did not decrease even after puberty suppression for adolescent girls. The report was so damning that a governor of the clinic, Dr Marcus Evans, resigned, saying he feared the clinic was fast-tracking youths to transition to no good effect and, in some cases, to their harm.

Perhaps the greatest risk for the adolescent girl, who grasps at transgender identity as if it is the inflatable ring she hopes will save her, is that she’ll wake up one morning with no breasts and no uterus and think: Why didn’t anyone stop me?

An increasing number of young women are now asking this question. They are those who once identified as transgender and later stopped, as well as those who underwent medical procedures to alter their appearances, only to regret it and scramble to reverse course.

Each one I talked to told a similar story – of having had no gender dysphoria until puberty, when she suddenly discovered her trans identity online. Also, they spoke of being 100 per cent certain that they were definitely trans – until, suddenly, they weren’t. Nearly all are plagued with regret.

Lucy, whose mother prompted my investigation, spent three months on testosterone, but stopped because it made her feel horrible. She did not have ‘top surgery’ and no longer identifies as a trans man. But she is left with a masculine voice.

Another girl was left in agony from uterine atrophy – thinning of the vaginal walls – caused by taking testosterone. The only way to alleviate the pain was a hysterectomy. When she awakened without a uterus, she realized her entire gender journey had been a terrible mistake.

Nearly all of these detransitioners blame the adults in their lives, especially the medical professionals, for encouraging and facilitating their transitions rather than questioning them.

Many drawn into the transgender world are already battling anorexia, anxiety and depression. They are lonely, fragile and, more than anything, they want to belong. ‘This isn’t necessarily about gender at all,’ says therapist Sasha Ayad.

Some families go to great lengths to move their daughters away from the schools, peer groups and online communities that relentlessly encourage their self-destructive choices. This is often successful. The mother of one girl who developed sudden gender dysphoria sent her to live on a farm for a year. The physical labor helped her reconnect to her body, and the lack of internet allowed her to leave her trans identity behind.

My message is this: young women should stop taking sex stereotypes seriously. A young woman can be an astronaut or a nurse; a girl can play with trucks or with dolls. And she may find herself attracted to men or to other women. None of that makes her any less of a girl or any less suited to womanhood.

Girls are not defective boys. They are different. They possess a whole range of emotions and capacities for understanding that boys, in general, do not. If only we didn’t make them feel so bad about this.

Tell your daughter that she’s lucky. She’s special. She was born a girl. Being a woman is a gift, containing far too many joys to pass up.

© Abigail Shrier, 2021