Download the entire post as PDF >

True to its origin. Not false, counterfeit or imitating. Free from corruption, influence, or distortion.

Krishnamurti observed, “we are second hand human beings,” enchanted, domesticated by selfish images, culture, their conditioning and conflicts. Our authentic nature is corrupted and distorted. We have been warned. From Genesis to Plato’s Cave, Lao-Tzu, Goethe’s cautionary poem, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and its unintended consequences. Yet, very, very few awaken from the dream. Most see little more than shadows dancing on the cave wall. History is not on our side.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama invites us to discover the reality behind appearances. Our tacit acceptance of things as they seem is called ignorance, which is not just a lack of knowledge about how people and things actually exist but an active mistaking of their fundamental nature. His central theme is that our skewed perceptions of body and mind lead to disastrous mistakes, ranging from lust at the one extreme to raging hatred at the other so that we are consistently being led into trouble as if pulled by a ring in our nose…. He describes how to harness the power of meditative concentration with insight to achieve immersion in our own ultimate (authentic) nature. To develop in us a clear sense of what it means to exist without misconception. And the way this profound state of being enhances love by revealing how unnecessary destructive emotions and suffering actually are.

Jeffery Hopkins, Translator, How to See Yourself as You Really Are

We don’t really understand the nature of our thought process; we’re not aware of how it works and it’s really disrupting, not only our society and our individual lives but also the way the brain and nervous system operate, making us unhealthy or perhaps even some way damaging the system.

To center our thought on something illusory which is assumed to have supreme importance is going to disrupt the whole process and it will not only make thought about yourself wrong, it will make thought about everything wrong so that thought becomes a dangerous and destructive instrument all around.

David Bohm, with Michael Mendizza

David continues by describing why simple and clear observations like those above, and centuries like them, fail to awaken us from our enchanted images of self and other.

We are faced with a breakdown of general social order and human values that threatens stability throughout the world. Existing knowledge cannot meet this challenge. Something much deeper is needed, a completely new approach. I am suggesting that the very means by which we try to solve our problems is the problem. The source of our problems is within the structure of thought itself.

The state of the mind that creates the problem can’t solve the problems it creates. That too is simple and clear. So, what do we do? As Bohm, the Dalai Lama and rare others invite, we stop trying to unite our mental knots with concepts that create more knots.

Instead, with care and clear attention, we ‘try’ to shut-up. But, even that often fails. Trying evokes the same system that the ‘trying’ hopes to negate. “Something much deeper is needed, a completely new approach.” Appreciating this paradox, we discover that the source of our problems is the ‘state of the mind,’ not its content. After all, content trying to change or eliminate content is still content. Ah, there is nothing we can do. No effort to be made.

As Ram Dass observed, ‘we have to give it all up to have it all.’ So, we relax. Stop trying. Suddenly the tension in the brain caused by trying, by thinking and hoping to achieve, like a clenched fist, releases. Conscious awareness expands, including, embracing and becoming everything it beholds. Behind what we consider to be ‘reality,’ with its conditioned memories, judgments, concepts and fears, is another ‘state,’ vast, ever-present-entangled-presence that has existed for millions of years. Perhaps forever. And this, not our social conditioning, responds, dances, improvises something new, creative, nurturing and whole. That spontaneous newness is authentic.

Prior to 10,000 years ago, all of human existence was precivilized, representing what we will call ‘primary-perception,’ the state of the human brain before the development of organized civilization—typically before writing, cities, and formal governments. Authentic refers to this precivilized mind. The best term for this original mind is “Indigenous,” “First Nation, “or “Aboriginal,” referring to the earliest human mind, and how this species typical state, if allowed, expresses with pristine intelligence today.

We discover from this historical view that there are two different states or realities active, authentic, representing 95% to 99%, and enchanted or domesticated, representing 1% to 5% of our species evolution. Which reality or mindspace is driving our personal and world affairs today? How well are we doing? What can we do to improve, assuming we can do better? That is our inquiry.

We know the human brain evolved in stages, with earlier structures like the brainstem and limbic systems forming first, followed by more advanced regions like the neocortex and prefrontal centers. Each layer adding new capabilities while still relying on older systems. Symbols, words and complex abstract concepts, thought as we use it, float on top of deeper, primary perceptions.

When we drop into awareness without naming or conceptualizing, thought-enchanting images disappear. We access layers of consciousness that predate language and ego. Neuroscience and psychology suggest this state taps into deeply embedded human traits like presence, trust, aliveness, and interconnectedness, qualities that are foundational to how we experience the world before thought intervenes:

Complete Attention and Presence: The ability to fully inhabit the moment without distraction, the raw experience of “being here now,” unfiltered by mental commentary.

Trust and Safety: In non-conceptual awareness, fear and judgment dissolve, revealing a baseline of basic trust. A deep-seated feeling that the world is fundamentally safe and good.

Aliveness. A not-named felt sense of vitality and energy.

Interconnectedness: Without the boundaries imposed by thought, the sense of separation fades leading to a feeling of unity with nature, others, and the cosmos.

Curiosity and Wonder: Not filtered through concepts, the world appears fresh and mysterious. Childlike openness is a primal mode of perception, unburdened by assumptions.

Compassion and Empathy: When ego quiets, defensiveness and judgment soften, allowing innate empathy to surface. Many traditions view this as the natural state of the heart.

Being compulsively identified with thoughts blots out these defining qualities.

Being aware without naming or thinking is like standing at the edge of a vast, silent lake at dawn—no ripples, no labels, just presence. Raw experience before the mind begins to carve it into words. A sensation of aliveness that is ‘known’ without needing to be understood. The warmth of sunlight on skin, the sound of a birdcall, the rhythm of breath—each arising and fading without commentary. There’s no “I” watching, no “thing” being watched. Just open, effortless noticing.

Like space itself: boundless, still, and quietly luminous. Let’s use these qualities as our working definition for ‘authentic,’ rather than words or concepts.

Authentic, or Primary Perception and its spontaneous action is not however, our norm. Quite the opposite, we name, dissect, separate, judge, and defend all sorts of imagined images.

We are racists, bigots, identified with nations, sects, political ideologies and beliefs, without critical attention to their virtual reality. We accept without hesitation what others say, even paid propaganda. So powerful and evocative are these mental images that they take on a life of their own. We lose track of direct perception and became enchanted, infected really, by the virtual realities we imagine.

This awesome power to enchant is blinding, extinguishing primary perception, its authentic qualities and deep, primal intelligences, as we grow increasingly dulled by technology. Think, for example, how far personal computers zoomed in forty-five fast years from the first Apple II and IBM models, 64K floppy disks to AI. Overwhelming. In our interview, Jerry Mander, author of “The Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television,” and “In the Absence of the Sacred: The Failure of Technology and the Survival of the Indian Nations,” described how Western civilization lives increasingly in its imagination, at the expense of social, spiritual and ecological balance. The 1% dominating the 99%.

Once the ego is formed, a fundamental virtual reality that distracts and blinds, this newly formed image uses thought to define itself, “I am this, not that, and so are you.” To control reality, “I must fix, change, or avoid…” To protect its assumed identity, “I’m right, I’m better, I’m separate.” And to perpetuate an inner narrative that defends, “This means that…” This narrative is often a loop, reinforcing reflexive patterns. Brilliant for survival and planning—but obscuring the deeper, quieter intelligence available in non-conceptual awareness.

The nested nature of our human brain displays a multi-layered moving image, what we call reality, as a blended display of our original and enculturated minds. Strip away the storytelling, the mythic overlays, and the world’s so-called spiritual practices attempt to balance primary human sensitivities with the awesome tool called imagination and intellect. The goal of these traditions is to allow our authentic nature, with is intelligences, to use intellect, not the other way around. The challenge is; epigenetics took its cues from our bloated and unchecked imaginations, rendering our authentic nature a distant dream. Can we find our way back to the future? Maybe.

In the abridged paper below, “The Missing Mind: Contrasting Civilization with Non-Civilization Development and Functioning,” by Darcia Narvaez and Mary S. Tarsha, EDN is the ‘Evolved Developmental Niche.’ It represents how human beings are treated from birth and early childhood and how this early experience sets our interpretation templates for a lifetime.

It is important to keep in mind how proprioception creates the embodied mental feeling of being separate from the living-moving world, a strong physical precondition for the inner feeling of a psychological ‘I’ or ‘self’ as we know it. Thought and ego are two sides of the same coin. The ego end with the ending of thought.

Proprioception is your body’s ability to sense its position, movement, and balance without relying on vision. It’s what allows you to walk, reach, or maintain posture without constantly watching your limbs. Proprioception predates vertebrates. This suggests it evolved hundreds of millions of years ago, possibly during the Cambrian explosion (~541 million years ago). Proprioception is considered a “sixth sense” because it operates largely outside conscious awareness, yet is vital for nearly every physical action.

Resting on this foundation, the development of agriculture and domestication of animals brought about a profound shift from egalitarian “small band hunter gatherers,” to the “selfish-civilized.” Culture led to possessing and hoarding ‘stuff.’ The powerful images of a “separate self” the intellect made of proprioception exploded, pushing all other ‘states’ off the table. Sages invited a rediscovery of our missing mind, mostly singing to deaf ears. There is an unconscious and overpowering predisposition of the 1% to negate and ignore the 99%. So, the beat goes on, with exponential streams of day dreaming enchantments now empowered by technology, compounding each generation, right up to the brink.

The Missing Mind: Contrasting Civilization with Non-Civilization Development and Functioning, Darcia Narvaez and Mary S. Tarsha*

Civilization began perhaps around 10,000 years ago and represents a fraction of the total kinds of societies that have existed. Considered timewise, civilized societies make up less than one percent of humanity’s presence on the planet. Prior to the gradual emergence of herding and farming communities, over 95% of humanity’s existence was spent as small-band hunter gatherers (SBHG), which are still present (Lee & Daly, 2005). These societies are matrifocal, where motherhood and the feminine principle of life were respected (Goettner-Abendroth, 2013).

The focus is on meeting basic needs and living well within the cycles of the natural landscape, with high social wealth, rather than emphasizing hierarchical power and competition which may have first started to appear with the practices of herding animals (Holden & Mace, 2004) and deep tilling of the soil (Bram, 2018). In fact, after holding an initial bias toward patriarchy as a baseline for what is species typical, anthropologists are coming to realize the centrality of mothering and child raising in our ancestral environments (e.g., Lee, 2018), and science is increasingly noticing the matrifocal egalitarian nature of ancient societies, not only among First Nations (Mann, 2006) but civilizations such as the early Egyptian and Minoan (Bram, 2018).

We briefly describe SBHG societies, focusing on one aspect which contrasts greatly with current civilization’s practices, the evolved developmental niche (EDN). Emerging from the social mammalian line tens of millions of years ago, the EDN supports the longstanding cooperative nature of our species which is apparent in SBHG (Ingold, 2005), but not so much in countries like the USA. Contrasting EDN effects with what civilized children usually experience, we present a sampling of capacities that have diminished or are overlooked in civilized persons as a result of these societal alterations.

For example, SBHG spend much of their mindspace in polysemy. Polysemy, in this context, is where consciousness swims in a shape-shifting world–there is no solid identity of a thing (Bram, 2018). Polysemy reflects the ability to merge with multiple others, human and non-human and is the product of de-differentiation, finding oneness with others rather than difference and separation. Many non-civilized cultures de-differentiate and creatively respond to the present moment, which is heavy with connection to others, including the other-than-human, to ancestors and other spiritual aspects of a dynamic, fluctuating universe. This inclusive creative space is where they spend/spent most of their lives. When needed, SBHG move into the problem-solving mindspace of univocity—linear logical thinking helpful for solving a particular problem. Though SBHG use both mindspaces, polysemy and univocity, with the rise of the Sumerian and subsequent civilizations, there was a shift toward spending more time in univocity, the problem-solving space brought on by stress.

Bram (2018) describes the gradual shift away from polysemy across the history of western civilization due to multiple factors including settled agriculture, forced labor imposed by elites, which led to increased hierarchy, writing, measurement and control of people and things, including war and slavery. Univocity depends on differentiation: sorting, categorizing, and abstracting. Differentiation makes distinctions, defining each thing as one thing only. Univocity relies on dualistic, dichotomous logic (something is or isn’t), emphasizing causes and effects which rely on linear thinking. The sense of the present is minimal as people are caught in trying to predict the future based on what was noticed from the past. Obsession with order, precision and prediction becomes normalized—all left hemisphere concerns (McGilchrist, 2009). These skills are valuable and necessary for both an individual and community to solve problems but according to McGilchrist and others (e.g., Tweedy, 2021) become distorted without the help of the right hemisphere’s global integration.

As a result of obsessive differentiation (sorting and naming separate objects), civilization creates a singular world with a hierarchical shape, a pyramid of order based on linguistic structure (subject-predicate-object) that becomes the model for logic (universal statement particular statementconclusion) and is transformed into social law.

For Bram, hypotactic (hierarchically-arranged) societies are made up of bits, separate entities, whether people, offices, assembly lines, or power structures. Persistent differentiation, encouraged by (noun-based Indo-European) language and law, leads to a hierarchical society that uses contests to determine who reaches the top of the pyramid. Contest winners take the top position—or top abstraction in fields of study like science, or in realms of life like religion or schooling.

Univocity plays a significant role in keeping the domination hierarchy in place to benefit those with more privilege. People get categorized, abstracted and coerced into their place. Punishments become part of life and orderliness becomes paramount. Life becomes about staying in your place and carrying your load.

The clash of these vastly different consciousnesses was apparent when European explorers, settlers and anthropologists encountered societies existing primarily in polysemy, but also in paradox – that is, a combination of diffuse or peripheral awareness in combination with focused attention or mental alertness (Berman, 2000). Europeans were confused by community members’ lack of precise definitions, shifting stories and social configurations, and their lack of leaders. They were not “logical” in the linear, univocal sense. At the same time, First Nation peoples remarked on the soullessness of European invaders, their inflexibility and lack of openness and awareness of a sentient Earth (Narvaez, 2019).

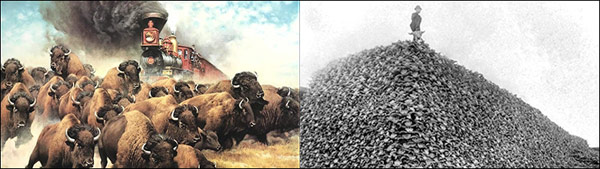

Note: For example, the Great American Buffalo Slaughter was a catastrophic period in the late 19th century when tens of millions of American bison were killed, reducing their population from over 60 million to just a few hundred by the early 1880s.

Showing similarities to Bram’s analysis, anthropologist E. Richard Sorenson (1998) noted a “preconquest consciousness” (versus postconquest consciousness in westernized nations) among the different Indigenous Peoples with whom he lived around the world over decades. Among those with preconquest consciousness, Sorenson documented the shifting descriptions of self, others and places, based on context.

There were no fixed identities. So, for example, a person could have multiple names that came or went, whose use shifted with the desire of mates or context. With the lack of fixed or rigid identities, the overall sense of the world was not static but dynamic, with actions changing and dependent on foregrounding, activity, season and mood, rather than on fixed cognitive thought.

The difference between univocity and polysemic consciousnesses appears to align with left hemisphere-dominated and integrated modes of being, respectively. Also similar to Bram’s analysis, McGilchrist (2009) reviewed empirical research on left and right brain functioning and then concluded that a lack of hemispheric integration (minimal right hemisphere involvement) and left-brain dominance has characterized most of Western civilization.

Left-brain dominated thought is governed by the explicit and the disembodied, oriented to static, categorizable things, interested only in what is preconceived or has a defined purpose. It focuses on detail, mechanistic processes, perfectionistic thinking and is largely more comfortable with impersonal interactions. The left brain contains more myelination within itself, indicating its function to refer to information that is known (self-referring), unlike the right brain whose expanded myelination and connectivity to the whole brain allows for perception and intake of new information outside itself, playing an integrative role in broad, generalized thinking (Tucker, Roth & Blair, 1986). The left-hemisphere’s skills are not in and of themselves deleterious. Rather, they are enhanced and balanced only when in dialogue with the right hemisphere (Tweedy, 2021).

The right hemisphere is able to ground and make sense of the detailed, perfectionistic and impersonal insights provided by the left. When bi-hemisphere collaboration occurs, one maintains the ‘big picture,’ responds to an evolving, dynamic, interconnected, world and is comfortable with obscurity (vagueness or mystery) and the personal, maintaining connections with the natural world and other systems (McGilchrist, 2009). According to McGilchrist, capacities for the diffuse, wide-open attention especially declined with the ascent of the Enlightenment and the West. The lack of hemispheric integration coupled with lopsided hemisphere leadership (left over right), led to an emphasis on materialism at the expense of social cohesion and respect for individuality—the unique nature of each person was replaced with categorical descriptions, such as race or socioeconomic status. McGilchrist points out that the common modern condition—feeling fragmented, devitalized, depersonalized, depressed, or dissociated, along with lost emotional depth and empathy—correspond to an overbearing left hemisphere and underactive right hemisphere—what psychotherapy seeks to rebalance (Tweedy, 2021).

Berman (2000) suggests that a large part of western civilization reflects disconnection from nature and from flexible coordination with others, including the other than human. In our view, the lack of connection to others, including to the natural world, generates further disconnections within the individual as well as the individual’s understanding of present and future life. According to Bram (2018), persistent differentiation leads to deep anxiety and death terror as the sense of the present is thin and emptied out of creative polysemy and the focus is on the future which will bring about certain death.

In contrast, integration of hemispheric functioning, the right-brain leading, results in thinking that is open and receptive, attuned to the energies of the moment, dominated by a feeling of relation and multiperspectivalism, interested in penetrating mysteries and that which is beyond apparent perception or comprehension; such integration is apparent in noncivilized communities the world over (Berman, 2000; Descola, 2013; Wolff, 2000). This type of hemisphere integration is able to drink deeply of the realities of the present moment, participatory consciousness, as well as conceive, creatively and realistically, the future. Moreover, brains that are integrated across hemispheres are associated with compassionate and kind action (Tweedy, 2021).

Like Sorenson, McGilchrist, Berman and Bram, physicist David Bohm (1994) also described two types of awareness. The first, insight-intelligence, the source of creativity, is open to the flow of shared being with others outside the self. It taps into transrational reality where participation is entwined with observation, instilling a sense of awe. For westernized minds, it appears in eureka moments. Among First Nation societies, it is routinely experienced in dreams, visions and intuitions (Wolff, 2001). For others, in participatory ceremonies, rituals and dances, sometimes with mind-altering practices. Bohm’s second form of awareness is thought-in-the-mind, a dualistic, subject-object worldview familiar to westerners. It consists of static habits of mind, a fossilized consciousness, such as beliefs and other self-referential or cultural loops. It is the self-looping of the left hemisphere. Cognitively speaking, we can see a lining up of polysemy with insight-intelligence and the right hemisphere, and a lining up of univocity with left hemisphere self-referential thought.

Taken together, we suggest a correspondence between the socio-cultural transformation and the biopsychosocial. That is, diminishing polysemy with the rise of patriarchy and the devaluing of women and natural cycles may be caused by the devaluation and degradation of nurturing child formation. We propose that a significant causal factor in bringing about the emphasis on univocity is the “misraising of the species’ brain,” that is, the lack of EDN provision, leading to an underdevelopment of coordinated connection to others and right-hemispheric functions generally. Specifically, it is our hypothesis that civilizations’ concern for controlling nature and non-elites led to a diminishment of EDN provision which became culturally sanctioned, leading to an enhancement of left-hemisphere functions at the expense of right hemisphere functions.

Darcia Narvaez describes how Western culture, with its emphasis on individualism and abstraction, expresses a developmental imbalance—favoring intellect over emotional and relational depth—especially when compared to the communal, ecologically embedded lifeways that defined most of human history.

There is, of course, a monumental challenge. Our reality has been domesticated for centuries. We can’t use our misraised, adulterated reality, a very powerful and convincing reflex indeed, to rediscover our authentic nature. Reality isn’t simply what happens—it’s how we feel or interpret what we experience. Ultimately, the brain doesn’t just process reality—it ‘represents’ it. Whether we feel safe, loved, and connected—or anxious, alone, and threatened—depends largely on how the various brain centers where shaped early in life. Early neglect, for example, disrupts the development of the limbic brain by impairing emotional regulation, memory formation, stress response, and social bonding. These early imprints can lead to long-term psychological and behavioral filters that color and distort what we experience as reality. A problem can’t be solved at the level the problem.

So again, how do we get back to the future appreciating as David Bohm suggests; “the ‘state’ that created the problem is the problem.” There is only one correct answer. We need to discover another ‘state’ that grounds our consciousness in primary perception, which then acts to reinterpret reality. It is only from this state that the limitations if thought and its enchantment are revealed. Let’s touch on two, mindfulness and beginner’s mind.

In classical Buddhist teachings, mindfulness—known as sati—is the practice of maintaining clear awareness of the present moment, grounded in ethical and contemplative discipline. In early Buddhist texts, sati is not just passive awareness—it’s an active, discerning attention that helps one observe thoughts, emotions, and sensations without attachment or aversion. Mindfulness is deeply ethical—it’s not just about being present, but being present in a way that cultivates wisdom and compassion. Practicing mindfulness helps one break habitual patterns. To see things as they truly are, without distortion. And to cultivate inner peace and clarity that supports ethical living and unconflicted wholeness. Stripping away the cognitive features and benefits, being mindful is a shift of ‘state,’ from enchanted participant to becoming aware, in the moment, of how consciousness and therefore behavior is organized and express. A shift from watching the show to a behind the scenes appreciation of how the show is created.

Being an enchanted participant in our hallucinated reality involves a dull, hypnogogic, semi-daydreaming quality of energy and attention. In David Bohm’s terms, our ordinary day-to-day levels of attention and awareness is that, low and dull, with implicit heightened suggestibility. Heightened suggestibility is a hallmark of both hypnosis and the hypnagogic state. In both, the mind becomes uncritically open to ideas, images, and associations, as in Henny Penny’s “the sky is falling.” A perfect ground for digital propaganda and social conditioning. Mindfulness, on the other hand, involves cultivating a quality of attention that lifts consciousness out of what David calls the mechanical and unintelligent ‘reflex system’ of habitual mental images.

Beginner’s Mind does the same. The concept of beginner’s mind (or shoshin in Zen Buddhism) refers to maintaining an attitude of openness, eagerness, and freedom from preconceptions—even when engaging with something familiar. It’s about seeing the world as if for the first time, like a child might, without the filters of past experience or expertise clouding perception. Beginner’s Mind involves Curiosity: A desire to explore and understand without assuming you already know. Humility: Recognizing that there’s always more to learn. Openness: Being receptive to new ideas, perspectives, and possibilities. Presence: Engaging fully in the moment without distraction from past knowledge or future expectations.

While knowledge is essential, beginner’s mind can be even more powerful in creative problem-solving. Experts may become trapped in conventional thinking and dogma. A beginner’s mind allows for out-of-the-box ideas and novel solutions. In learning new skills: letting go of the fear of being wrong or looking foolish can accelerate learning and experimentation. Navigating change: In unfamiliar or rapidly evolving situations, rigid knowledge can become outdated.

Beginner’s mind fosters adaptability and resilience. Interpersonal relationships: Approaching others without assumptions encourages empathy, deeper listening, and more meaningful connections.

Leadership and innovation: Leaders who embrace beginner’s mind are more likely to ask fresh questions, challenge the status quo, and inspire innovation. As the Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki famously said: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert, there are few.”

The magic key to unlock your authentic nature abides in the body, not the mind as we know it. The states called mindfulness and beginner’s mind represent a simple yet profound shift in the state of the human, brain, body, attention and perception. From unenchantment we begin to discover and feel the brain, body, attention and perception change when enchantment, what we consider to be our normal state, habitually returns. This feeling difference, not the idea, concept, will, or grasping, is the yellow brick road back to our true nature. Returning to our senses breaks the spell and we now recognize the difference.

One of the best stories that illustrate this was told by Achyut Patwardhan, a significant figure in Indian political and philosophical circles who was closely associated with both Gandhi and Krishnamurti.

I remember an occasion when a Jain monk walked up, travel weary. He learned that Krishnaji was there and it was very urgent that he should see him. The monk said that he had been pursuing this problem of going beyond thought for years, and couldn’t make any headway. He had tried everything, all the austerities, and now he was at the end. He was about forty-six, and said he would just give up his food because if he could not achieve this there was no point in living.

Krishnaji smiled and said, “You are trying to find an answer, aren’t you, Sir? You are trying to find a solution. I would rather change this process and merely look at what you are trying to do with yourself. Look at what thought is trying to do with itself. Thought is trying to persuade itself and pressurize itself to stop its operations because it wants to get something out of it.

This is something thought can’t do. So, you have just to grasp the single fact that what you have been trying to do for fourteen years, which thought has been trying to do. And there is just no way by which thought will ever be able to do it. Just see the finality of it. It is not within the capacity of thought to do what you want thought to do. Just watch what thought is doing to itself and perhaps, if you do and wait….”

And suddenly there was a change in the appearance of the monk. He closed his eyes and he was quite silent. After about four minutes he opened his eyes that were full of tears and he touched Krishnaji’s feet and said, “Sir, I have been wanting to get this for a long and have not been able. So, thank you and I’ll go.”

Krishnaji said, “No, don’t be in such a hurry. Please sit for a few minutes.” And the monk sat quietly, but suddenly blurted out, “Sir, I have one more question to ask. Well, that was alright. Really, thought was absolutely quiet, without my doing anything about it. But, how can it last? How can I get it again?”

Krishnaji smiled, “I knew that is the question you were going to ask me. But who is it that asks the question? The mind that is silent is asking this question or the mind that was not able to get silent and worrying over it, is asking the question. It is again the old mind. You’ve gone back to the old mind and that old mind is asking this question because it wants to possess what you’ve got; it wants to hold onto it and continue it. All this is the normal function of thought. You had moved out of that room and now you want the answer in this room. That is, you want the answer to be with thought. Do you see what you are doing? Do you see it, Sir, what thought is doing to you? What thought is doing to itself?”

And again, the monk went silent and he opened eyes that were full of tears and he said, “Sir, I’ll not come to you again.”

Enchanting thoughts come and go, but our authentic essence remains. Our identity with thought evaporates when we awaken from the dream. With that, the endless falling into trouble as if being pulled by a ring in our nose also disappears. Samdhong Rinpoche refers to this “authentic,” unnamable essence as our Buddha Nature.

Whatever our lives are like, our Buddha Nature is always there. And it is always perfect. We say that not even the Buddhas can improve it in their infinite wisdom, nor can sentient beings spoil it in their seemingly infinite confusion. Our true nature could be compared to the sky, and the confusion of the ordinary mind (our thoughts, ego and identification with culture) to clouds. Some days the sky is completely obscured by clouds.

We should always try and remember: the clouds are not the sky, and do not belong to it. They only hang there and pass by in their slightly ridiculous and non-dependent fashion. And they can never stain or mark the sky in any way.

So where exactly is this Buddha Nature? It is in the sky-like nature of our mind. Utterly open, free, and limitless, it is fun, so simple and so natural that it can never be complicated, corrupted, or stained, so pure that it is beyond even the concept of purity and impurity. To talk of this nature of mind as sky-like, of course, is only a metaphor that helps us to begin to imagine its all-embracing boundlessness; for the Buddha Nature has a quality the sky cannot have—that of the radiant clarity of awareness. As it is said: “It is simply your flawless, present awareness, cognizant and empty, naked and awake.”

Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

End

*Narvaez, D., & Tarsha, M. (2021). The missing mind: Contrasting civilization with non-civilization development and functioning. In T. Henley & M. Rossano (Eds.), Psychology and cognitive archaeology: An Interdisciplinary approach to the study of the human mind (pp. 55-69). London: Routledge.